“PEOPLE LIKE US”

(as told to her daughter Susan Hearst)

Introduction

Maria Weyland (known to the family by the affectionate name Marisia) was born on the 27 February 1920 less than two years after the end of the First World War, “the war to end all wars.” She was born in the city of Lodz, an industrial city in Poland with a large Jewish population of approximately 200,000 people, one third of the total population.

My paternal family: the Weylands

I don’t remember my paternal grandparents, they both died when I was two years old. The family name was Weyland. My father Michal was virtually their only child, there was another son but he died very young. Michal and the Weyland family lived in Lodz. His parents Anna and Marcus Weyland both died in 1922.

My maternal family: the Feiffers

I remember my maternal grandparents very well, and I have pictures of them in my family album. My grandmother Rose Feiffer (nee Kol) was a small gentle woman but bearing ten children took all the guts out of her. She was still having her youngest child when her oldest daughter was having children. My grandfather Wolf was a tall, good looking and patriarchal man. I remember them celebrating their golden wedding anniversary with the whole family in Kalisz. The Feiffers were a large and colourful family of eight surviving children of which seven were daughters. My grandfather Wolf died when I was eleven years old; my grandmother Rosa was shot by the Germans at the age of eighty four when she was still in perfect health, with good eyesight and hearing. After returning from work I believe my Aunt Genia found her in bed with a neat bullet hole in her head.

Our life before the war

Lodz was the family home for the Weylands and the three children, Hala, Maria and Marcel. Michal was an industrial chemist by profession educated in Germany and worked in this profession as a representative of a Danish firm Aarhus Oliefabrik. As well he was a partner in a hosiery factory which was bliss for us girls.

We seemed to have been well-off though at the time I didn’t give it a thought. There was always a cook, and at first a nanny, then a governess for us children. A man used to come from my father’s office to do heavy cleaning. We always lived in sumptuous apartments and we all had an excellent education. Of course Marcel nearly missed out as he was only twelve years old when the war broke out. But even on the run he attended Russian school in Vilna, American school in Japan and British school in Shanghai, and the rest in Sydney.

The family took holidays at the Baltic seaside or Carpathian Mountains, school camps etc punctuated the year. I attended a private school at first then one of my uncles who was a doctor in the local government persuaded my parents to get me into a government school which he thought had a higher standard of education. I was rather unhappy at first, then settled down and had firm friends from both schools and until recently was still in touch with some of them.

My sister Hala married her longtime boyfriend Boleslaw Jakubowicz in Lodz before the war. They both had good education and Hala finished Commerce and Economics in Warsaw while Bolek had studied in Vienna. Bolek’s mother was Viennese. Hala and Bolek had excellent jobs in Lodz, Hala worked for a large newspaper “Republika” in administration. The newspaper belonged to Mary Polak’s husband and two other partners who both died in the war. They lived in a beautiful appartment in a building which belonged to the Wilenski family. At one stage the Weyland, Wilenskis and Rossleigh families all lived in the same apartment house. We had a rather grand appartment with two enormous reception rooms joined by sliding glass doors. Hala was married in this apartment.

1939-1941

I matriculated as dux of my class as my sister did before me. At this time the situation in Polish universities was not very pleasant for Jewish students [e.g. Numerus Clausus] so after long discussions with my parents I was enrolled at the lnstitut Supérieur de Commerce à Anvers (Antwerp) in Belgium.

In late August 1939 my father decided he wanted the whole family to return home to Lodz as there was going to be a war. So against my better judgement I boarded a Polish freighter in Antwerp and returned home in a roundabout way rather than go by train the direct way through Germany. I arrived home without any trouble and about a week later the war broke out. Early on the 5th of September we heard on the radio that the Germans were approaching Lodz, so just as we stood we got into the car, six of us, my parents, my sister Hala (Halina), my bother-in-law Bolek (Boleslav), and my younger brother Marcel who was twelve at the time. The car was Hala and Bolek’s, a Ford Eiffel, not too big, and as the time and space were too precious we took nothing but money and jewellery. We left Lodz thinking it would be only for a short time until things settled down, but as it turned out we never went back.

We drove towards Warsaw, the capital, under bombs all the way. Several times we had to get out of the car and hide in the ditches. Somehow we reached the outskirts of Warsaw where we ran out of petrol. It was impossible to get petrol as it was only for the military, so we just locked the car and left it by the side of the road. Perhaps it is still there, Bolek kept the key. Public transport to Warsaw was still operating. In Warsaw we reached the apartment of friends, and after a day or two we left with a larger group of people aboard a hired truck going east towards the Russian frontier. After driving some distance the truck had to be abandoned as we were sold water instead of petrol.

We pushed on east, at first in a horse-drawn carriage, and somehow got to Lublin and met the Gostynski family who helped us find somewhere to sleep. The next morning Lublin was bombed and we started travelling east on foot. On the way crossing a river my father twisted his ankle and we dragged him towards a small township near the Russian border. The town was Kowel, a Ukrainian-Jewish town. We stayed there until the Russians came, and according to their agreement with the Germans they annexed this east part of Poland. We queued up for food, tried to find relatives and friends in the great mass of humanity which passed through the township. After a few weeks we heard that Wilno (Vilna now Vilnius) a large Polish town near the Lithuanian border was to be given to Lithuania, which at that time was still a free country which had always claimed that Wilno was theirs by rights.

We waited at the railway station for three days and nights for the train to Wilno. Finally it came and hanging from doors and windows we scrambled aboard. A few days later we were in Wilno. This important and beautiful Gothic city was overflowing with refugees. But slowly things became organised, we rented rooms, the Lithuanians brought food, relief committees were established and refugee kitchens operated. Nobody went hungry; my mother ran a refugee kitchen which served two meals a day. We stayed in Lithuania for over a year. I looked after younger children, organised some lessons as there were no schools operating at this time. But all this time we did not feel secure, and my father constantly explored possibilities of getting out of Europe, although at first not very successfully. Then history stepped in, the Russians came back and that was the end of independent Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia.

1941: Our next exodus started

But people still hoped and tried to get away. In Kaunus, then the capital of Lithuania, there was a Dutch consul [Jan Zwartendyk] who tried to help the refugee Jews. He suggested that he would issue us with visas to Curacao (Dutch West Indies at the time). He also told us that we would never be allowed to land there, but perhaps we would be able to obtain other visas on the strength of the Curacao trick. And then thanks to the actions of Chiune Sugihara in Kaunus we managed to get a Japanese transit visa valid for ten days. Chiune Sugihara was the Japanese vice-consul appointed to Lithuania in 1939. His was a low-key official post, his main task being to collect intelligence from fleeing Polish officers about the state of the border between the USSR and Nazi Germany.

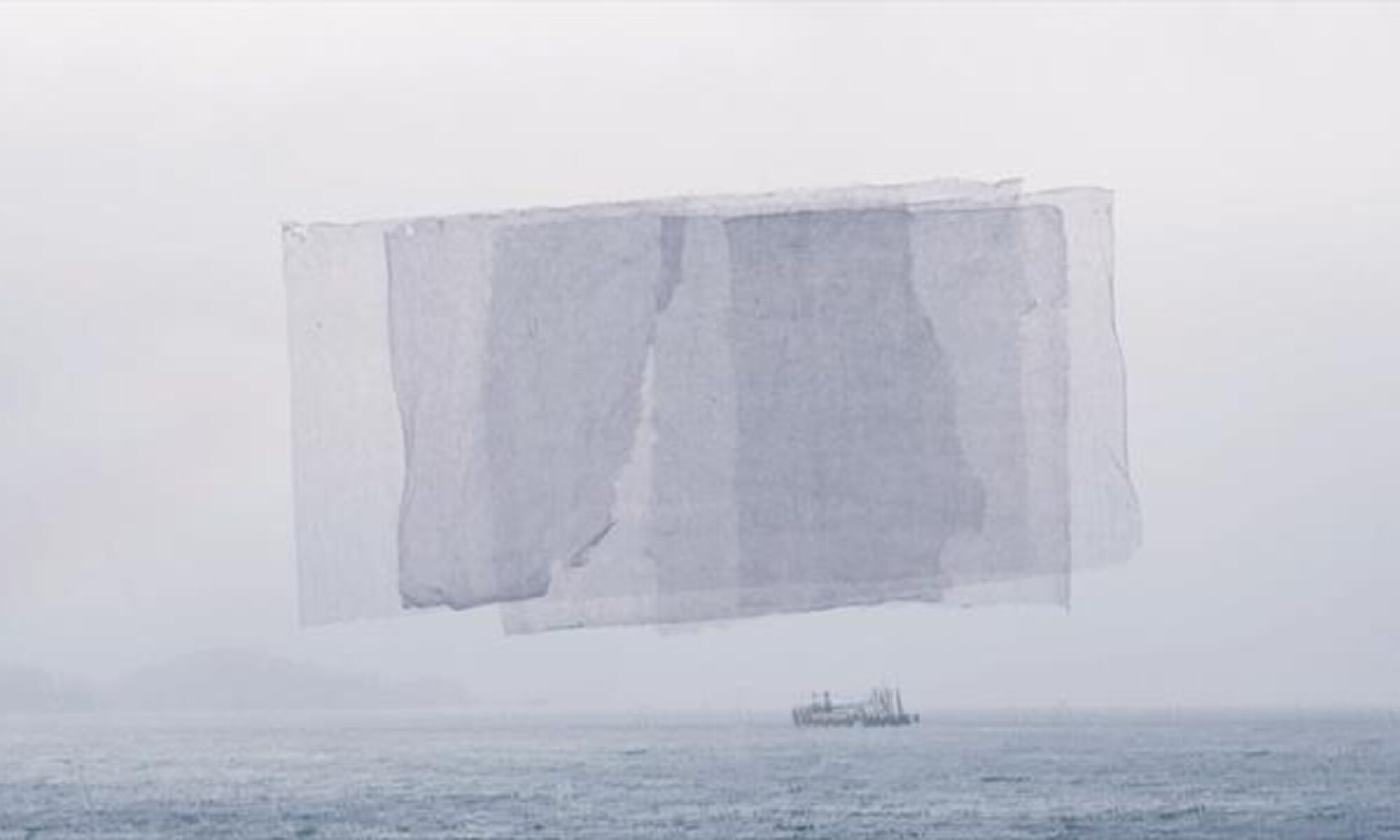

In the end we did pay in dollars for our trip, though with great trepidation, and finally in February 1941 we left Wilno for Vladivostok on the Trans-Siberian railway. About 1500 left Wilno in this way within a month, and one way and another we crossed Russia and arrived in Vladivostok, a journey of over two weeks. It sounds simple but it wasn’t. There were endless investigations by the Russian authorities in the middle of the night, and until the very end when we finally left Russian soil we were never sure if they would let us go. In Vladivostok the Russian Customs made a thorough search of our meagre possessions, confiscated watches and finally, finally we were escorted onto a tiny Japanese freighter, the Amakusa Maru, and departed for Japan.

The main worry was whether the Russians would let us go. It was a complicated affair. The Russians wanted to be paid in American dollars for the overland trip to Vladivostok. On the other hand it was illegal in the Soviet Union to travel with foreign currency and was punishable by law. It was a Catch-22 situation, all the more so because most of the educated, young refugees were told they would be allowed to leave if they agreed to spy for the Soviet Union wherever they ended up. People gave all sorts of excuses or agreed in desperation.

Kobe

We arrived after a crowded sea-sick crossing in April 1941. The cherry blossoms were in bloom, the whole countryside was covered in flowers and the petite Japanese in their kimonos were so picturesque that after weeks of going through Siberia and seeing nothing but snow, dirt and poverty, we thought we had arrived in Paradise.

We were taken to Kobe, a pretty town near Osaka and Kyoto. The family spent eight months there being helped by various relief agencies such as the Jewish JOINT from America and the Polish government in exile in London. We were treated well by the Japanese, but towards the end of our stay, when they knew they would soon be at war and we knew nothing, they got rather suspicious of us and we were followed wherever we went. Japan was preparing for war so all foreigners were treated as possible spies.

Meanwhile there was still a Polish Embassy in Tokyo, and the Ambassador, a very helpful man [Tadeusz Romer], tried to arrange permits for the refugees to emigrate. He managed to get some people to Canada, mainly to join the army there, also some to South Africa, about 100 to Australia and 40 to New Zealand. Time was short and the Japanese now wanted all foreigners out of Japan. All the unplaced people were packed off to Shanghai, where most spent about five years.

To Australia, via Shanghai

I had a Canadian permit but by this time the Japanese had broken off diplomatic relations with Canada, so I decided to go to Australia instead hoping that my family would follow. I left them in Shanghai in November 1941. We didn’t know that I would not see them for many years, and that I would never see my father again, as he died in Shanghai in 1942.

Saying goodbye to all of them was heartbreaking. I left Shanghai with a group of fifteen people, all going to Australia. We stopped in Hong Kong, Manila, the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), travelling on a Dutch ship which was half freighter, half passenger. We travelled in a complete blackout, rather slowly, and finally arrived in Sydney one week before Pearl Harbour.

This site is supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17K02041 / 18KK0031.